The Appalachian Trail trail stretches from Georgia to Maine and covers some of the most breathtaking terrain in America–majestic mountains, silent forests, sparking lakes.

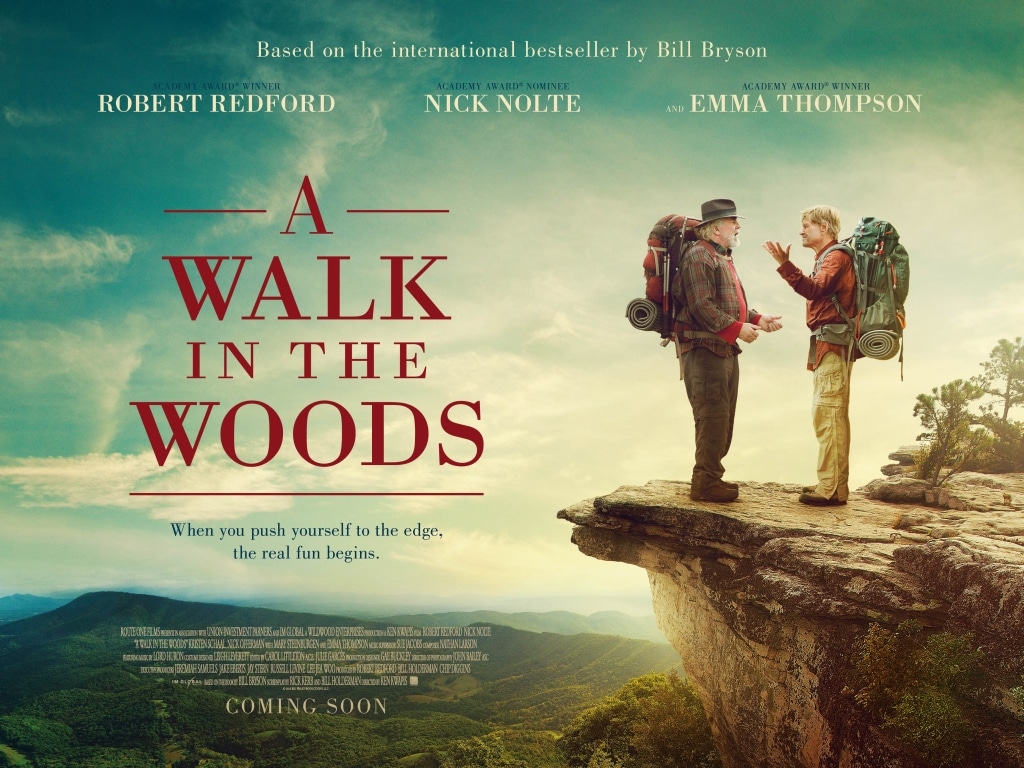

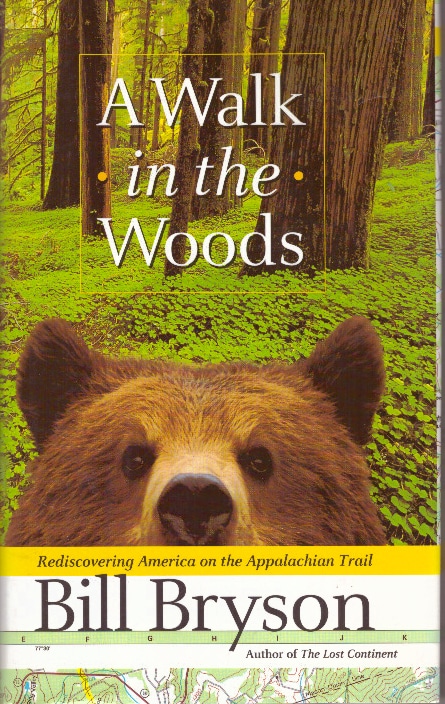

A Walk in the Woods

If you’re going to take a hike, it’s probably the place to go. And Bill Bryson is surely the most entertaining guide you’ll find. He introduces us to the history and ecology of the trail and to some of the other hardy (or just foolhardy) folks he meets along the way–and a couple of bears

Bryson has met this challenge with zest and considerable humor. He begins by scaring you a little. He tells you of the trail’s perils: its dangerous animals, killing diseases, “loony hillbillies destabilized by gross quantities of impure corn liquor and generations of profoundly unbiblical sex.” And bears that bite.

He tells you of the power of woods to unnerve. “The inestimably priggish and tiresome Henry David Thoreau thought nature was splendid, splendid indeed, so long as he could stroll to town for cakes and barley wine, but when he experienced real wilderness, on a visit to Katahdin in 1846, he was unnerved to the core.”

He tells you of his hiking partner, Stephen Katz, a childhood friend from Iowa who had been attracted to drugs and alcohol until he was found by the police “in an upended car in a field outside the little town of Mingo, hanging upside down by his seatbelt, still clutching the steering wheel and saying, ‘Well, what seems to be the problem, officers?”‘ Katz is seriously out of shape and given to seizures ever since he took “some contaminated phenylthiamines about 10 years ago.” Bryson remarks, “I imagined him bouncing around on the Appalachian Trail like some wind-up toy that had fallen on its back.”

When he gets through being scared, Bryson entertains you with the history of the trail, the hell of the early going when he and his partner were not yet conditioned, the quirky characters they met, the geology, biology, ecology of the terrain, and jokes. You turn the pages not knowing what’s around the next bend.

Then, after trudging for what seems like forever, he arrives in Gatlinburg, Tenn., and sees a map of the trail “about six inches wide and four feet high.” He writes: “I looked at it with polite, almost proprietorial interest — it was the first time since leaving New Hampshire that I had considered the trail in its entirety — and then inclined closer, with bigger eyes and slightly parted lips. Of the four feet of trail map before me, reaching approximately from my knees to the top of my head, we had done the bottom two inches.”

“My hair had grown more than that.”

He concludes: “One thing was obvious. We were never going to walk to Maine.”

“A Walk in the Woods” is a funny book, full of dry humor in the native-American grain. It is also a serious book. Nothing really terrible happened to the author, but by playing on our fears, he captures the ambivalence of our feelings about the wild. We revere it but we’re also intimidated. We want to protect animals but we also want to kill them. The woods are lovely, dark and deep, but they also “choke off views and leave you muddled and without bearings.” He continues: “They make you feel small and confused and vulnerable, like a small child lost in a crowd of strange legs.”

One other contradiction is also captured in these pages. Americans may be destroying their environment, wiping out species, mismanaging ecology, but our forests remain vast and impressive. “One third of the landscape of the lower 48 states is covered in trees — 728 million acres in all,” Bryson writes. “Maine alone has 10 million uninhabited acres. That’s 15,600 square miles, an area considerably bigger than Belgium, without a single resident. Altogether, just 2 percent of the United States is classified as built up.”

What’s more, in the past century and a half, the woods have reclaimed 40 percent of New England, Bryson writes. The feeling he leaves you with is that despite all our abuse of it, nature may be too powerful to take notice.

Bryson himself was liberated by nature’s vastness. The impossibility of walking the whole length of the trail freed him to sample it in stages. All the same, he ended up walking 870 miles of it — or 39.5 percent of its total — a distance slightly greater than that from New York to Chicago.